Publishing industry research reports based on large sample sizes can be an arduous task. They take a lot of time and meticulous planning, cost sizeable amounts of money, and are often funded by the researcher itself, especially when the topic is more ‘academic’ in nature. And no matter how much time and money you may choose to invest, you have to be prepared to accept that the outcome may not always be revelatory in nature. That after all the hard work, you may be told: “But I knew this all along!”

But all the effort, time and investment are worthwhile, because every now and then comes a report that breaks the “But I knew this all along!” template. With our latest study And the Remote Goes To…, we have hit this elusive sweet spot. The research, conducted in Oct-Dec 2020 (to negate any lockdown impact), was designed to answer a question that’s often debated in television channel offices but never conclusively answered: Who controls the television remote in an average family in India?

This study covered more than 5,000 urban Indian households across 29 states and union territories in the country, to profile the gender and the age of the ‘remote incharge’ in these households. For the purpose of this piece, we will look at only one aspect of the report: Gender of the remote incharge, i.e., is the person controlling the TV remote in an average Indian household a man or a woman?

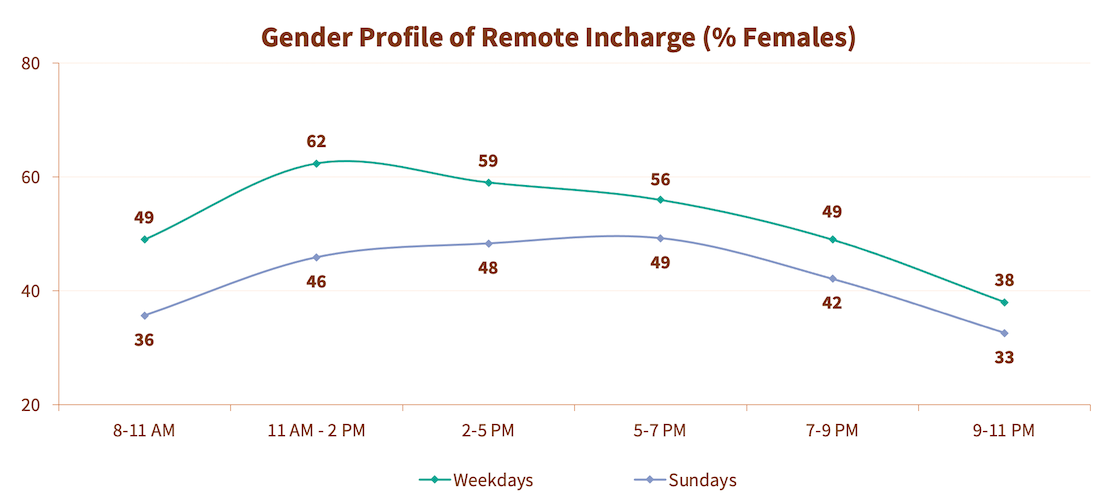

The chart below shows how the share of female control over the remote changes over a typical weekday and a typical Sunday. On weekdays, women control the TV remote in about 60% households in non-prime time. This proportion drops to 49% for early prime (7-9 PM) and then significantly to 38% for 9-11 PM.

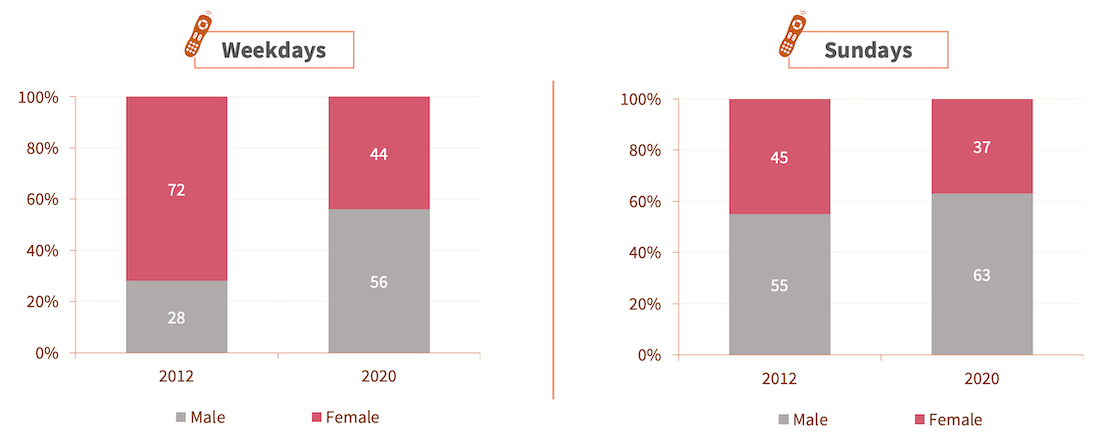

On the face of it, this can evoke that “But I knew this all along!” reaction. But that’s not the story here. As it turns out, we had done the same research, with the exact same design (albeit only for prime time) back in 2012 too. The chart below compares gender-wise control over the TV remote in prime time (averaged over 7-11 PM) between the two time periods.

Ignore the right side for a moment and take a hard look at the weekdays chart on the left. From 72:28 to 44:56, the female control over the TV remote in weekdays prime time has declined by a whopping 28 percentage points. It’s been just eight years, which is hardly a long period of time for change as significant as this, for a parameter as ‘social’ as this. One may have known one of the two data points all along, but the complete restructuring of the remote-control dynamics in urban Indian households is a story so compelling that it can be a subject of extensive research in the areas of both social studies and entertainment habits.

The shift is understandably a result of multiple factors, and a nuanced understanding would require further research. But here, in the rest of this piece, I have attempted to put forth my interpretation of what may have happened over the last eight years to warrant this dramatic ‘turnaround’.

To understand how control over the TV remote reached the female-led 2012 levels in a patriarchal society like India, we need to go back to 2000. Daily soaps were first introduced by Star Plus that year, and went on to change, forever, the way prime-time television is watched in India. Other channels and regional languages followed suit, and a battery of family dramas and love stories were launched over the next few years.

I’m not entirely sure if the woman (rather than the family) was the target audience for the original set of launches, such as Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi and Kahaani Ghar Ghar Kii. But sooner than later, it was apparent that this is the target group daily soaps appealed to the most. Men watched along, but the real emotional drive came from the women of the house, especially the married ones.

One has to put this understanding in context of India’s patriarchal social structure, in which the proportion of working women is abysmal (and lower in urban India than in rural India), and where women face day-to-day restrictions related to routine activities such as dressing, going out shopping for groceries, meeting their friends, etc. One day in 2000, all of a sudden, the married Indian woman found a friend in the form of her television set. This friend told her stories of other women, who were like her, but had that extra bit of zing (wealth, looks or smartness) compared to her, making the women in these stories relatable and aspirational in equal measure.

A window to the world outside opened up for her. For years, these stories and their lead protagonists were labeled as regressive by the media. But they were anything but that for the Indian woman, at least at that time. They gave her a peek into a world that can be, but never is. They gave her dreams, and changed the way she looked at her surroundings and her relationships. Anecdotes of women being ‘allowed’ to ‘express’ themselves in their sasuraal as a result of something shown in a TV show were not uncommon. A 30-something housewife once told us in a research that almost a decade after her marriage, her father-in-law finally allowed her to be physically present in the same room as him, because that’s a topic that came up in a daily soap, compelling him to reconsider his views on it.

Nature sets its rules in fairly intuitive ways. The member of the household who has a higher-order emotional connect with television would simply be allowed to control the TV remote. That’s how it panned out in a sizeable majority of Indian families post 2000. And that member, more often than not, was a woman.

Men, however, did not always like how their wives and daughters-in-law interpreted messaging doled out in the dailies. Some felt it will give women ‘wrong ideas’ about questioning patriarchy (Even today, a sizeable majority of Indian men believe working women cannot take care of their families like housewives can). This led to some amount of gender tension, which started peaking in 2005-06, which is also when ‘K-serials’ were beginning to lose their sheen.

But before this tension could escalate further, came in Colors. The channel changed the narrative overnight from urban stories to rural and small-town stories, often with kids and teenagers as protagonists. This is an aspect the married Indian woman had not explored via her television since 2000. Social topics tend to be more gender-inclusive too, and the gender tension around television content subsided, at least for a while, as the relationship of the woman with her dailies shifted from real yet aspirational to empowering and inspiring.

But there’s only so much a story can say. And there are only so many ways to tell the same story. By 2013-14, the empowerment agenda had been driven home. Hammered in, rather. There were no new issues left to explore. After all, how many times can you reinforce the theme of female education, for example? The Indian woman had got her messages, and she found that TV channels were now telling her what she already knew.

Coincidences work beautifully at times. Around the same time (2015-16), entered the smartphone. Till that point, the married Indian woman was dependent entirely on television for her world view. But now, she had another ally. It opened her mind to other ways of communication and messaging. WhatsApp may not be the most reliable source of information, but its ubiquity is undeniable. TV was not her only friend now, even though its video format ensured it remained her first choice for a few more years.

The gender tension was replaced by a new type of tension: The smartphone tension. This new form of disruption operated at a family level, creating worries that the grand Indian institution of the family may be under threat. Television, now, emerged as the saviour. From being a villain that could give ‘wrong ideas’ to the women of the house, it became the hero that helped families spend time together. Old notions of empowerment and inspiration gave way to new ideas of togetherness.

There is no personal TV viewing in India, which is a dominant single-TV (96%) market. The higher-order-emotional-connect argument mentioned earlier does not hold anymore. Both the husband and the wife are equally interested in keeping the family together, after all. The new hero of the house is now being propped up by them, not always to the liking of sub-15 members of the household (but that’s another story for another day).

And that’s where we are today. It’s 2021, and television has emerged as a gender-neutral medium. News, sports (particularly IPL) and movies have grown in viewership share, non-fiction shows have gained more traction, and daily soaps that target only the woman are struggling, especially in the Hindi language (remember, other languages are a few years behind on this curve, because they started later than 2000).

So, was the 2012 female skew an aberration, and the 2020 gender balance a desired state? That question is a complex one, and perhaps has more to do with society than with television anyway. Whatever be the answer, it is safe to say that the gender story around television viewing behaviour in India over the last two decades is more fascinating than the best of the stories we have seen on television itself during the same period.

You can download the And The Remote Goes To… 2020 report here.

Introducing Ormax Media Affluence (OMA)

OMA is a new audience classification system designed specifically to measure affluence level of audiences in context of the media & entertainment sector in India

Venn It Happens: OTT & Linear TV audience intersection

The first edition of our new feature Venn It Happens illustrates the intersection between OTT and Linear TV audiences in India, using data from The Ormax OTT Audience Report: 2025

Not just nostalgia: Why legacy characters are dominating HGECs

Despite not featuring in the show since 2017, Daya (Taarak Mehta Ka Ooltah Chashmah) continues to enjoy immense popularity among Hindi GEC audiences. Her enduring success highlights a category trend

Subscribe to stay updated with our latest insights

We use cookies to improve your experience on this site. To find out more, read our Privacy Policy