If you have been following the Hindi GEC category over time, the collectivistic culture that fiction shows in the category attempt to portray would not have escaped your attention. Many shows are set in large joint families, while others have multiple nuclear families that interact with each other so freely and frequently that they seem like a large joint family anyway.

But in a poorly-conceived show, this collectivism can come across as mere tokenism. You can see a lot of characters on screen filling the space, but many of them can be just scenery, not adding to the collectivist construct of the show. Hence, the number of speaking characters in a scene, than the number of visible characters, is arguably a more robust measure of a show’s collectivist construct.

But this line of thinking may seem presumptuous, unless we can prove that a stronger collectivist construct is more likely to yield a hit show vis-à-vis a show where this construct is weaker, all other things being equal.

An analysis of speaking characters in 14 Hindi GEC shows over the 2019-21 period was conducted to test the hypothesis above. Seven hit and seven flop shows across the mainline Hindi GECs were selected. The definition of hit and flop is based on the viewership ratings trend of the show over its lifespan. Some of the shows classified as “flops” may not have been washouts. But they were certainly not “hits”.

For each of these 14 shows, 50 randomly-selected episodes were chosen. In each of these episodes, two randomly-chosen time-codes were selected, and the number of characters who speak in the entire scene that’s running at that time-code were counted. Hence, a total of 1,400 scenes were analysed, 700 each in the hit and flop categories.

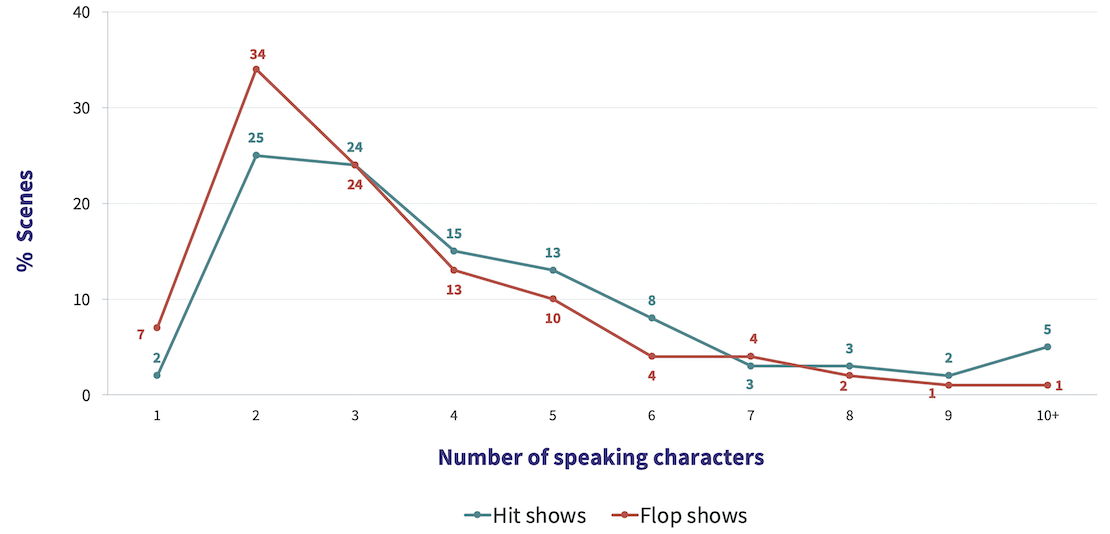

The chart below plots the distribution of these scenes for the two categories, i.e., the percentage of scenes that had a specific number of speaking characters. The red line (flop shows) peaks earlier than the green one. As many as 41% scenes in the flop shows has only one or two speaking characters, compared to only 27% scenes in hit shows.

Another noteworthy area in the chart above is the 4-6 characters zone, which accounts for 36% of hit show scenes, compared to only 27% scenes in the flop episodes. And then, there is a significant spike at the right end of the chart, where hit shows have 5% scenes with 10 or more characters speaking in them, compared to only 1% such scenes in flop shows.

Is this difference between the two sets statistically significant? The answer is an emphatic yes. Because of the large sample of scenes studied, it can be statistically established (using an unpaired, one-tailed T-Test, for those interested) with more than 99.99% confidence that the number of speaking characters in a randomly-chosen scene from a hit Hindi GEC fiction show will be higher than those in a randomly-chosen scene from a flop Hindi GEC fiction show.

If we look at a simple average of the same data, an average scene from a hit show features 4.2 speaking characters, vis-à-vis 3.4 speaking characters in an average scene from a flop show. This difference of just one character can be the crucial difference between a show succeeding or failing.

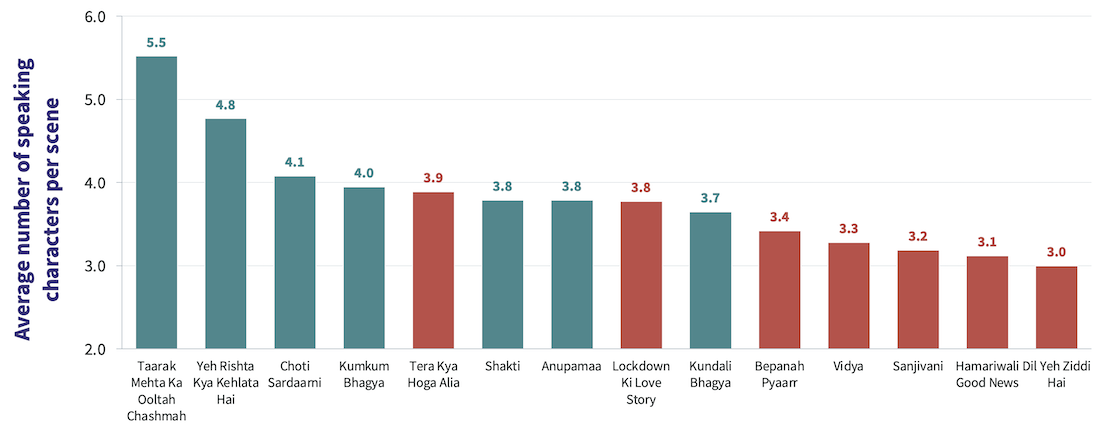

Is this pattern consistent across shows? The chart below plots the seven hit shows (in green) and the seven flop shows (in red) based on the average number of speaking characters in the scenes in each of them.

At the top of the list are long-running hits Taarak Mehta Ka Ooltah Chashmah and Yeh Rishta Kya Kehlata Hai. The former has a staggering 17% of its scenes featuring 10 or more speaking characters. No other show even crosses 5% on this measure!

While all hits show average at 3.7 or more, two flop shows are not too below the four-characters mark, indicating that four speaking characters in a typical scene is a necessary but not a sufficient ingredient in the recipe of a hit Hindi GEC show.

Clearly, it’s a case of ‘the more, the merrier’. Hindi GEC storytelling champions collectivism, be it in celebrations, facing challenges together or taking on life journeys that intersect with each other’s. There may often be one or two central protagonists driving the story, but it’s the ensemble around them that gives them wings to fly.

Four vs. three is probably not a coincidence. In Indian culture, four has traditionally been associated with being the minimum ‘acceptable’ size of an Indian family. Three is a group alright, but not a family. And without a family, of some form or the other, the idea of collectivism is not easy to realise. At least not on Indian television anyway.

So, here’s a talking point to take back from this analysis: Make four characters talk in most scenes and your show may still flop. But make three or less talk in most scenes and it will almost certainly not be a hit.

Ormax Trac20: Ad & sponsorship effectiveness research for IPL 2026

Our new tool Ormax Trac20 combines weekly ad tracking and multi-stage brand lift diagnostics to help IPL 2026 sponsors & advertisers measure impact and optimise in-season performance

Introducing Ormax Media Affluence (OMA)

OMA is a new audience classification system designed specifically to measure affluence level of audiences in context of the media & entertainment sector in India

Subscribe to stay updated with our latest insights

We use cookies to improve your experience on this site. To find out more, read our Privacy Policy