By Shailesh Kapoor, Amit Bhatia, Gautam Jain

Over the last year, there’s been an incessant industry debate on the topic ‘theatrical vs. OTT’. But very little hard data has been used to make this debate meaningful from a business perspective. This report attempts to plug that gap.

When the 2020 lockdown resulted in prolonged closure of movie theatres, producers and studios were tempted with lucrative offers by streaming platforms to release their films directly online, or ‘direct-to-OTT’, as it’s often referred to. The first Hindi film to go online was Shoojit Sircar’s Gulabo Sitabo, which premiered on Amazon Prime Video on June 12, 2020. At the time of publishing this report, 26 Hindi films (and several others in regional languages) that were originally conceived for a theatrical release have taken the direct-to-OTT route, including last week’s Netflix release Haseen Dillruba. Netflix has showcased nine of these, Amazon Prime Video and Disney+ Hotstar six each, and ZEE5 the remaining four, including those through its pay-per-view offering ZeePlex. With the re-opening of theatres still uncertain, quite a few other titles are scheduled for a direct-to-OTT release in the coming weeks. Only a few big ones like Sooryavanshi and 83 have held back, hoping for a theatrical release soon.

What has been the extent of box office loss as a result, we are often asked. Through this report, we hope to answer that question. The analysis that follows is based only on the 26 Hindi films mentioned above. Regional films have not been considered in these projections. The list of 26 includes Salman Khan’s Radhe: Your Most Wanted Bhai. While the film had a theatrical release overseas, it had to go direct-to-OTT in India.

Methodology

Two statistical models were used for our projections. The FBO (First-Day Box Office) Model deployed by our film tracking tool Ormax Cinematix was first used to estimate the likely opening of each film, if it had released on its originally-planned date (including 'clashes', if any), and in a COVID-free scenario. This also means factoring for extraneous variables like holidays, IPL, examinations, etc. Using benchmark data from films with similar theme, starcast and trailer response, an estimate of each film’s box office opening (FBO) was calculated. For films that did not have a theatrical release date announced, a ‘regular Friday’ release was considered.

In the next step, the LBO (Lifetime Box Office) Model deployed by our script and film testing tools Ormax First Draft and Ormax Moviescope was used to project the FBO to an LBO estimate. This model uses the Ormax Power Rating (earlier called Ormax Word-of-Mouth) as a key input. OPR is a single-number measure on a 0-100 scale that captures the core strength of the content, and hence its ability to sustain for a longer period.

OPR of the 26 films is available because these films have already released on streaming platforms. However, this OPR is for a streaming release, which does not mirror the theatrical reality, either in terms of the audience profile or the content experience. Using a TG mapping exercise, OPR from streaming was converted into a theatrical estimate. For example, Laxmii’s OPR increases from 45 (streaming) to 52 (theatrical estimate), while that of Ludo reduces from 66 (streaming) to 61 (theatrical estimate). The estimated theatrical OPR was used to projected each film’s FBO to its LBO, accounting for clashes and holidays, if any.

The Results

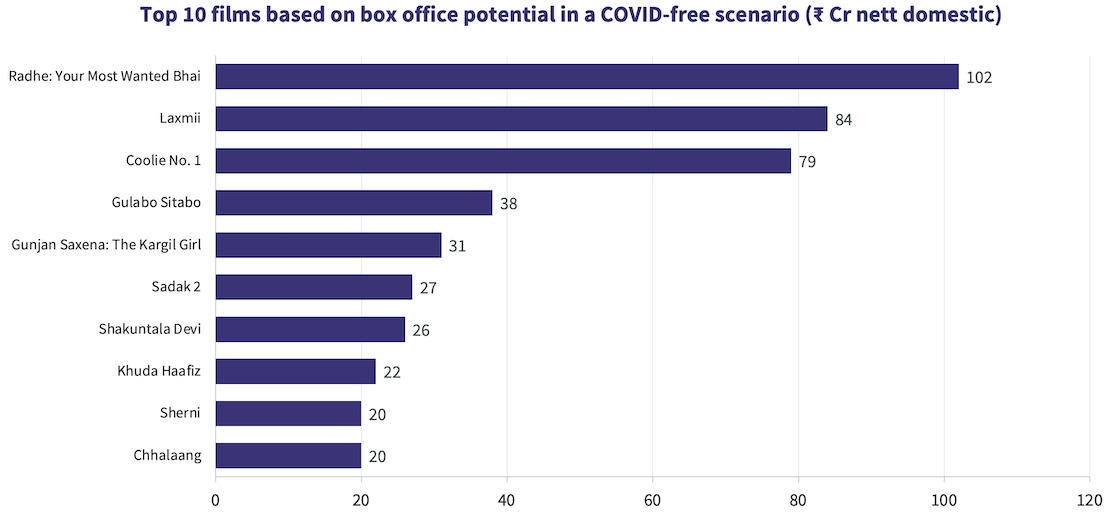

Based on the analysis, the total domestic box office potential of the 26 films in question has been estimated at ₹ 580 Cr nett, i.e., post tax deduction. 10 films, seen in the chart below, cross the ₹ 20 Cr mark, contributing to 76% of the ₹ 580 Cr figure between them.

Anyone who follows Hindi cinema’s box office even occasionally would know that ₹ 580 Cr is a modest number across 26 films. The estimates of the top 3 films in the list explain why the total number is so low. These three films would have been expected to register collections in the range of ₹ 400-500 Cr between them. They have fallen well short of that expectation. And there’s no ‘surprise’ film in the list, the equivalent of (say) Badhaai Ho or Chhichhore, to compensate for the sub-par performance at the top.

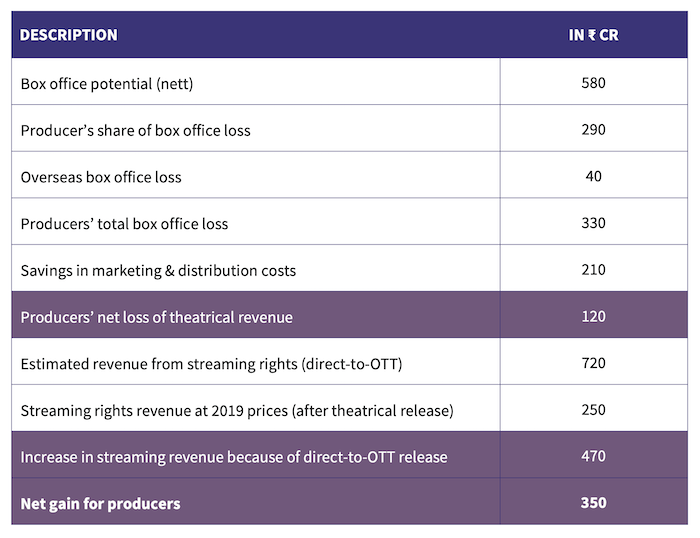

The entire ₹ 580 Cr would not have come to the producers, of course. Exhibitors would have taken their share (taken at a ballpark 50%). The loss incurred by the exhibition sector, which relies on multiple sources of revenues, because of COVID-19 is another story altogether, for another day. From the producers’ perspective, the estimated loss at the domestic box office stands at about ₹ 290 Cr.

There’s also the small matter of overseas box office. We call it ‘small’ because many of these titles would not have released overseas, and the content of others is not exactly aligned to the overseas market’s taste. An estimated loss of share of about ₹ 40 Cr has been considered from the overseas box office, not considering Radhe, which released overseas anyway. That takes the total estimated box office loss at the producer end to ₹ 330 Cr.

But here’s the big twist. A producer or a studio incurs marketing and distribution costs when it releases a film theatrically. This cost ranges from ₹ 5-20 Cr per film. The marketing of these films was handled by the streaming platforms directly, leading to a huge cost saving at the producer end. At a modest average of ₹ 8 Cr marketing and distribution budget per film, that’s a saving of ₹ 210 Cr for 26 films, which brings down the box office loss at the producer end to only ₹ 120 Cr.

A Win-Win Situation

But the ₹ 120 Cr figure does not tell the complete story. After all, these films were sold to streaming platforms at much higher prices than they would have been sold if they got a launch window on streaming only after their theatrical release.

Based on industry estimates, the total monetization from streaming rights across the 26 films stands at a staggering ₹ 720 Cr. If these films had released theatrically, pre-COVID streaming acquisition prices suggest they would have collectively garnered about ₹ 250 Cr via streaming rights.

Satellite prices have been largely unaffected. Some of the niche films were acquired by streaming platforms for satellite too, to ensure exclusivity. But such films don’t rate much on TV anyway, because of which they don’t find takers for satellite rights too easily.

So, we have an estimated revenue gain of ₹ 470 Cr from streaming rights, which more than offsets the ₹ 120 Cr loss at the box office, resulting in a whopping net gain of ₹ 350 Cr for the producers. If you have lost track of the numbers, here's a summary:

One could argue that there are other types of losses too, such as those related to delays in monetization. While we have chosen to stay away from quantifying such subjective factors, it is safe to say that even if they had been factored in, the ₹ 350 Cr number estimated above will not reduce by more than a small fraction.

So, that’s where things stand. Hindi film producers have earned about ₹ 350 Cr more than what they would have, if there was no pandemic, from these 26 films. Not that the streaming platforms are complaining. Premiering these films have allowed them to widen their audience base considerably over the last year. No web-series, however high-profile, can be as effective in acquiring new subscribers in India currently as a mainstream theatrical-worthy film. And streaming platforms know that now, with real examples.

Why would one release a film theatrically at all then, if this direct-to-OTT business model is more lucrative? There are at least two reasons. One, this entire analysis would have looked very different had Sooryavanshi and 83 chosen to go direct-to-OTT. Because the numbers look what they are because of the absence of those big ₹ 150-200+ Cr grossers at the top. Two, the price premium streaming platforms paid in 2020 can be seen as marketing cost to acquire new subscribers. Those price points are simply not sustainable over time.

So far, it’s been a win-win situation for both producers and streaming platforms. The exhibitors have suffered, of course, and their losses don’t have corresponding gains to show. As we prepare for theatres to re-open, hopefully sooner than later, the pandemic has given a genuinely lucrative model for small films, which often struggle to even recover their marketing costs. But for the likes of Sooryavanshi, 83, Laal Singh Chaddha and KGF: Chapter 2, the big screen still beckons.

Ormax Cinematix's FBO: Accuracy update (February 2026)

This edition of our monthly blog summarises Ormax Cinematix's box office forecasts (FBO) for all major February 2026 releases vis-à-vis their actual box-office openings

Ormax Trac20: Ad & sponsorship effectiveness research for IPL 2026

Our new tool Ormax Trac20 combines weekly ad tracking and multi-stage brand lift diagnostics to help IPL 2026 sponsors & advertisers measure impact and optimise in-season performance

OWomaniya! 2025: Quantifying gender diversity in Indian entertainment

The fifth edition of the OWomaniya! report by Ormax Media & Film Companion Studios, presented by Prime Video, reveals glaring statistics on gender disparity in the Indian entertainment industry

Subscribe to stay updated with our latest insights

We use cookies to improve your experience on this site. To find out more, read our Privacy Policy